24. June 2025

“If I really have to write everything down, I’ll never get finished!” – Anyone who has dealt with corporate knowledge management knows this problem. At the same time, one often hears the complaint: “Even the simplest things are not done correctly!”

So how can you find the right level of detail in knowledge documentation despite these conflicting requirements?

Free yourself from outdated assumptions and focus on your target audience! With the following tips, you can achieve noticeably higher production efficiency and fewer unplanned downtimes in your manufacturing – even with changing or inexperienced machine operators.

“If I write down everything in detail, at least mistakes won’t happen.”

Humans are not computers that reliably execute every line of code. Our short-term memory can store a maximum of 6–7 pieces of information. Try it yourself by having someone tell you phone numbers of different lengths and try to remember them. Especially when people need to combine several pieces of information and keep them in mind at the same time, they quickly reach their limits.

In addition, we are evolutionarily conditioned to achieve necessary results with the least possible effort (energy use). Some call this laziness; at the same time, it is often the source of creative solutions. Either way, once knowledge entries reach a certain length, our brain evaluates the shorter time of “just trying” – even with lower probability of success – as the better option. As a result, overly detailed documentation often goes unread.

“With reasonable people, you can assume quite a lot and don’t need to write everything down.”

Unfortunately, this assumption cannot be applied universally. The human brain is very good at associating. Basic knowledge we already have can easily be transferred to similar things or situations. Someone who can drive a car will probably manage a tractor relatively quickly, and the switch from Windows 7 to Windows 11 succeeds because we can connect it to existing knowledge.

It’s different when the basic knowledge and the mental models associated with it are completely missing. Someone who has never worked in automated production will be overwhelmed even by small problems. Nothing is generally “logical” or “intuitive” – access is always associative. This principle is largely independent of intellect. When people “act dumb,” what they usually lack is the necessary basic knowledge.

Therefore, you need to identify the overlap in basic knowledge within your target group to decide what you can assume and thus don’t need to document. A useful indication is often a person’s professional background. If you want to support a former baker or a former nurse working at a thermoforming machine, you will probably need more detailed documentation than with trained automotive mechanics.

Especially in times of staff shortages, companies are onboarding people from different backgrounds. That makes structured knowledge management more critical than ever.

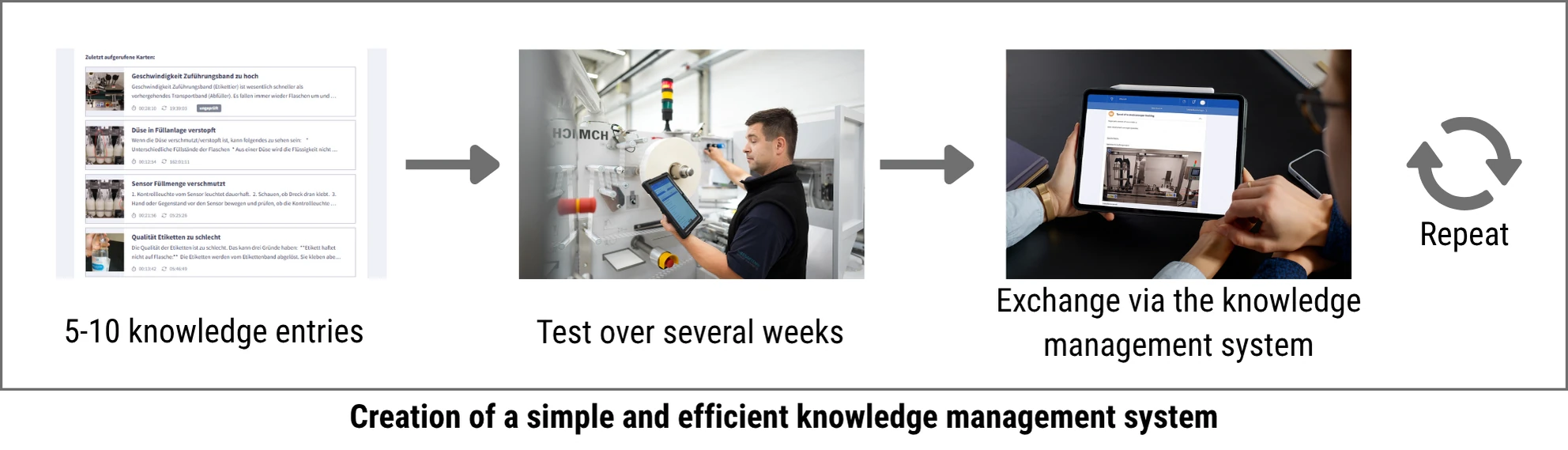

1. Start Small

Write a small number (5–10) of knowledge entries on the most frequent/relevant topics. Choose the level of detail intuitively, based on your knowledge of the target group. Lower your expectations a little and settle for about 80% completeness at the start (Pareto principle).

2. Test the System in Practice

Introduce the knowledge management system as a trial in practice and communicate about it.

3. Use Questions as Feedback

In most cases, your colleagues will not yet use the new system as intended and will still turn to you as an experienced person if you are nearby. Use this by referring them to the relevant knowledge entry and “staying close for further questions.” This way you achieve three things:

a. You lower barriers, because you are still available if questions arise.

b. Colleagues learn: “If I ask a question about something that’s in the new knowledge management system, I’ll be referred to it anyway. So I might as well use it first.” Over time, this shapes the habit of using the system.

c. You can observe how the target group uses the documented knowledge without them

Production Downtime and Operator Response: What Causes Slow Reactions – and How to Reduce Downtime.