13. January 2026

Good knowledge management isn’t measured by the amount of stored documents, but by one central question: Does the needed knowledge reach the right person at the right time? In production, this means concretely: Can a machine operator immediately access the experience a colleague had with the same problem two years ago when a disruption occurs? Or does this knowledge remain invisible—in one employee’s head, in a hard-to-find document, or in a system that simply isn’t used in daily work?

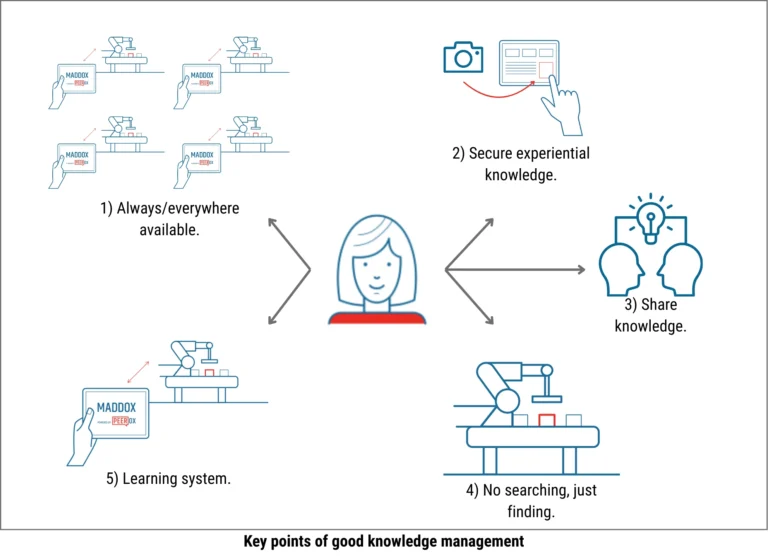

Good knowledge management fulfills several core principles:

Knowledge must be available and usable when it’s needed—not stored somewhere, but actively accessible within the work context. A system that lies outside the daily workflow gets bypassed. Integration into existing processes determines acceptance. But availability isn’t the same as applicability. Only when knowledge is prepared in a way that’s understandable and actionable in the specific context does it have an impact.

Experiential knowledge must be captured before it leaves the company. The implicit knowledge of experienced specialists is often the most valuable asset—and the most fragile. For it to enter the system, capturing it must be seamless. If documenting experiences feels like bureaucratic overhead, the system stays empty. Low barriers determine whether knowledge gets captured at all.

People must be motivated to share and search for knowledge. This doesn’t happen by itself. Sharing knowledge often feels risky; searching for knowledge requires effort. A good system reduces these barriers instead of ignoring them.

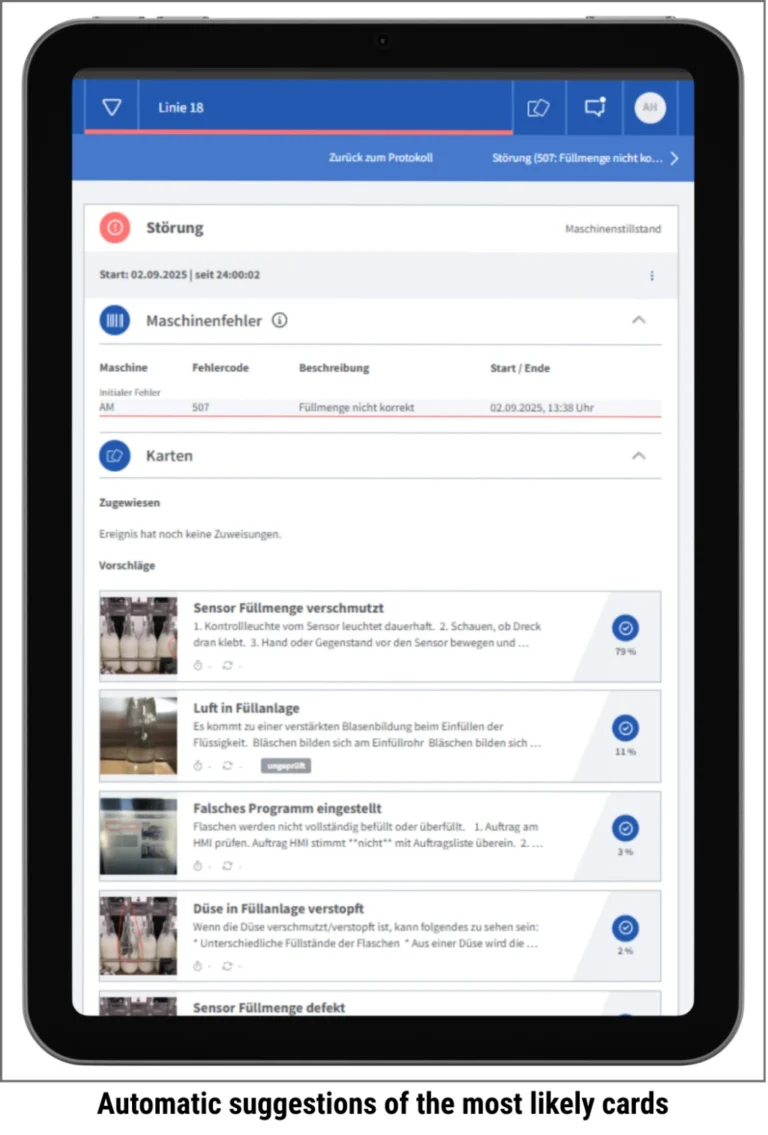

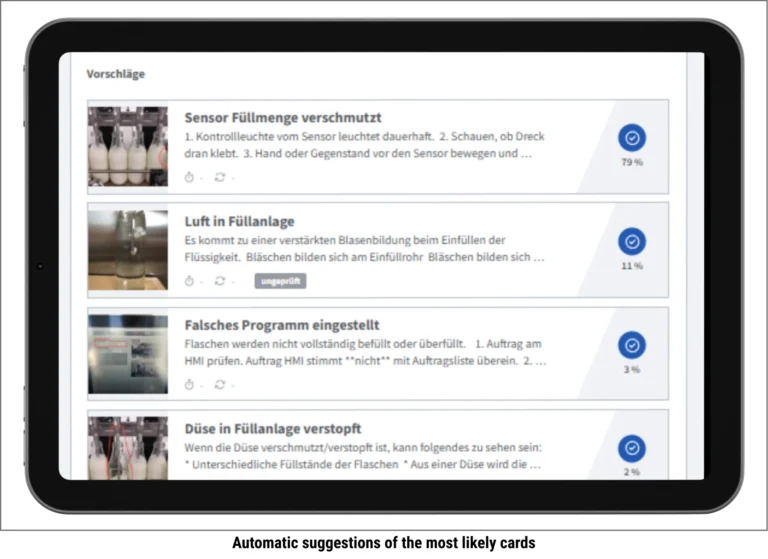

Knowledge should come to the employee—not the other way around. Systems that require active searching lose out in day-to-day production. Relevant knowledge must appear at the right moment without having to be asked for.

Knowledge isn’t static. Processes change, machines get updated, new insights emerge. A good system learns along with them—it grows and stays current.

Technology can enable the flow of knowledge—but not force it. What matters is whether the solution fits the workflows, whether it gains acceptance, and whether it brings knowledge to where it’s needed. That’s a question of concept, not features.

Want to learn more about implementing knowledge management to reduce production disruptions? Our whitepaper provides you with solid foundations and a detailed practical guide. What do I need to consider when implementing knowledge management?

Modern AI systems process large amounts of data in real time, recognize patterns in complex datasets, and continuously improve their results through machine learning. This gives AI enormous potential for knowledge management in production.

But these capabilities are tools, not ready-made solutions. The crucial question is: In what form and with what concept can this potential actually be harnessed?

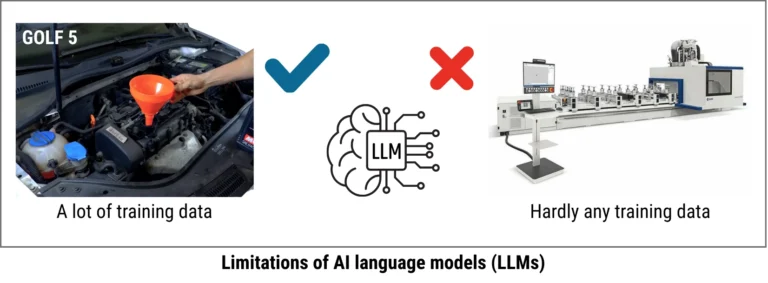

With the rapid development of large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, the topic of knowledge management suddenly seems solved. That’s why many companies are currently focusing on deploying this technology, which is (incorrectly) equated with “AI” in everyday language. However, some fundamental limitations should be considered here—limitations that won’t be resolved anytime soon, even with the rapid advancement of these models.

If you ask large language models about a specific problem, you usually get a very good, concrete solution (aside from possible hallucinations). For example:

“I need to change the oil in my Golf 5. How do I do that?”

But with a production disruption, you typically don’t know the underlying problem—and finding it as quickly as possible is the core expertise of human experts. That’s why LLMs are comparable to traditional knowledge management systems without data connectivity, which help experienced employees with very targeted search queries. With vague symptom descriptions like:

“I’m getting a product jam at the outfeed of my thermoforming machine. How do I fix this?”

you either get a long, generic list of results, or the LLM starts a dialogue. The latter is especially common with Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) based systems with corresponding data sources in the background. In the end, the language model navigates you through a fault tree, just like human customer support has been doing on hotlines for decades. And what’s been your experience with that so far? It can work, but it’s usually annoying and takes forever, right?

So what if you gave LLMs additional context information, for example in the form of machine data? Admittedly, the models have gotten noticeably better at data analysis recently, but they remain language models that can only handle time-series data and binary signals from machine controllers in a very limited way. The underlying transformer technology isn’t the right approach for that.

Then there’s image recognition, where the latest AI generation also delivers impressive results. Here, production practice simply fails due to the availability of training data. Try uploading a photo of a complex machine with a non-obvious problem and getting information about the cause. Most likely, the model—especially with custom machines—has never “seen” a close-up of that particular module, let alone the disruption. No matter how good the models are, they’ll only have a real chance once corresponding training data from industry is openly available in sufficient quantities—which won’t be the case anytime soon.

It’s sometimes forgotten that AI existed before November 30, 2022 (the release of ChatGPT 3.5), with a huge range of algorithms for very different use cases. Among them are specialized machine learning methods for pattern recognition in typical time-series data from production processes. These learn quickly and are still performant enough to run on standard hardware on-premise.

And the missing training data from industry? It already exists—as the experiential knowledge of employees who work at the machines every day. This knowledge is often a company’s most valuable asset. The question is how it gets into the system. When sharing becomes as easy as taking a photo or a short video at the machine, experiential knowledge becomes usable. When your own experience visibly contributes to a solution, motivation increases. This creates the fuel that AI needs—not from external sources, but from within the company itself.

The starting point should be the problem, not the technology. Those who truly understand the challenges of knowledge management in production—why knowledge isn’t found, why systems aren’t used, why experience is lost—and who know the principles that make good knowledge management, can develop a solution that deploys AI where it has its strengths. Not as an end in itself, but as an enabler.

This creates a system that doesn’t wait for an employee to ask the right question. It recognizes the situation—a disruption, a pattern, a context—and delivers the appropriate solution on its own. Knowledge appears when it’s needed. Not because the technology dictates it, but because the principles require it. When a solution is developed on this foundation, the result isn’t simply digitalization—but a fundamentally better way of handling knowledge in production.

LLMs remain a useful complement—for example, for more efficiently writing or logically structuring knowledge entries. But they don’t form the foundation.

Sources:

https://www.mister-auto.at/tutorials/volkswagen/golf-5/wie-volkswagen-golf-5-1-4-16v-motorol-und-olfilter-wechseln/

https://www.dds-online.de/bauelemente/fenster/fuer-komplexe-aufgaben/